Threads in Patañjali’s Wisdom

Thank you for registering for Threads in Patanjali’s Wisdom online course with Dr. Agi Wittich This page contains everything you need for eight weeks

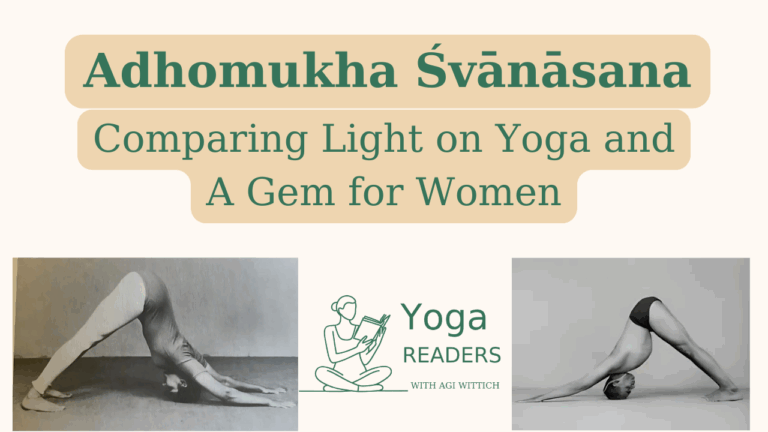

Adho Mukha Śvānāsana, commonly known as Downward-Facing Dog, stands as perhaps the most recognizable symbol of yoga practice in the Western world. This seemingly simple yet complex asana appears in virtually every yoga sequence, from beginner classes to advanced practices. However, beneath its familiar exterior lies a rich tapestry of instructional approaches that reveal profound differences in yogic pedagogy and philosophy.

This analysis examines how two seminal works from the Iyengar tradition present this fundamental pose: B.K.S. Iyengar’s “Light on Yoga” and his daughter Geeta S. Iyengar’s “Yoga: A Gem for Women.” While both texts emerge from the same lineage, their approaches to teaching Adho Mukha Śvānāsana illuminate distinct pedagogical philosophies that reflect broader conversations about accessibility, adaptation, and the nature of “classical” yoga practice.

The Classical Foundation: Iyengar’s Architectural Approach

In “Light on Yoga,” B.K.S. Iyengar presents Adho Mukha Śvānāsana with the precision of an architect designing a monument. His instructions begin from a prone position, emphasizing the methodical construction of the pose from the ground up. The key elements of his approach include:

Structural Precision: Iyengar’s instructions focus on specific anatomical landmarks and their precise positioning. He emphasizes “keeping the elbows straight and extending the back” while “placing the crown of the head on the floor.” This approach treats the body as a geometric structure where each element must be precisely aligned.

Duration and Intensity: The recommendation for a 60-second hold reflects Iyengar’s belief in the transformative power of sustained poses. This extended duration allows the practitioner to move beyond the initial muscular effort into a state of stability and awareness.

Therapeutic Mentions: While Iyengar does acknowledge that this pose can serve as an alternative for those who fear or cannot perform headstand, and notes its suitability for those with high blood pressure, these mentions appear almost as afterthoughts to the primary instruction.

The genius of Iyengar’s approach lies in its unwavering commitment to an ideal form. As he states: “place the crown of the head on the floor, keeping the elbows straight and extending the back.” This creates a clear target for practitioners to work toward, establishing what we might call the “classical blueprint” of the pose.

The Adaptive Framework: Geeta Iyengar’s Inclusive Vision

Geeta Iyengar’s approach in “Yoga: A Gem for Women” represents a fundamental shift in pedagogical philosophy. Rather than beginning with the “perfect” pose and expecting students to adapt to it, she begins with the understanding that bodies are diverse and creates instruction that meets this diversity head-on.

Sequential Entry: Her method begins from Tāḍāsana (Mountain Pose) through Uttanasana (Forward Fold), creating a logical progression that helps students understand the pose’s relationship to other asanas. The specific measurements she provides – legs 120-135 cm apart, hands 30-35 cm from feet – offer concrete guidance for spatial relationships.

Systematic Modifications: Rather than treating modifications as exceptions, Geeta Iyengar presents them as integral parts of the instruction:

Shorter Duration, Different Focus: Her recommendation of 15-20 seconds with emphasis on normal breathing and gentle movement reflects a more process-oriented approach. Rather than holding for endurance, the focus shifts to quality of experience and sustainable practice.

The Philosophy of Adaptation

The contrast between these approaches reveals a fascinating philosophical divide that extends far beyond a single pose. Iyengar’s method embodies what we might call “aspirational pedagogy” – presenting the ideal form and trusting students to work toward it over time. This approach has the advantage of maintaining clear standards and preventing the dilution of traditional forms.

Geeta Iyengar’s approach, however, represents what we could term “inclusive pedagogy” – recognizing that the pose must serve the practitioner, not the other way around. Her systematic inclusion of modifications acknowledges that the inability to achieve the “classical” form doesn’t represent failure but simply a different starting point.

What’s particularly noteworthy is how Geeta Iyengar addresses limitations without necessarily attributing them to specific medical conditions. Her language – “those who cannot,” “those who find it difficult” – normalizes the experience of physical limitation without pathologizing it. This creates what she describes as “a teaching envelope that begins with the classical pose but directly addresses a wide range of physical conditions.”

The Modular Architecture of Modern Yoga

This comparison reveals how a single pose can become “a rich field of variations and modular layers with different adaptations that address every situation where the body cannot implement the ‘classical’ position of the pose.” This modular approach has profound implications for how we understand yoga practice in the 21st century.

The beauty of Geeta Iyengar’s system lies in its recognition that yoga must be practical to be transformative. By providing specific tools for different physical realities, she creates a framework where the essence of the pose – its actions, intentions, and effects – can be experienced regardless of anatomical limitations.

Implications for Contemporary Practice

These different approaches to Adho Mukha Śvānāsana reflect broader questions that face modern yoga:

Tradition vs. Accessibility: How do we maintain the integrity of traditional forms while making yoga accessible to diverse bodies and abilities?

Standards vs. Individualization: What constitutes “correct” practice when bodies and circumstances vary so dramatically?

Process vs. Product: Should we focus on achieving specific forms or on the quality of attention and awareness that yoga cultivates?

The comparison between these two texts suggests that these questions don’t require choosing sides but rather understanding that different approaches serve different purposes and populations. Iyengar’s precise standards create a container for deep practice and study, while Geeta Iyengar’s adaptive framework ensures that this container remains accessible.

Conclusion: The Living Tradition

The evolution from “Light on Yoga” to “A Gem for Women” represents not a departure from tradition but its natural evolution. Yoga has always been a living practice, adapting to the needs of its practitioners while maintaining its essential wisdom. The fact that both approaches emerge from the same lineage demonstrates that authenticity in yoga is not about rigid adherence to form but about the intelligent application of principles to serve human flourishing.

In Adho Mukha Śvānāsana, we see a microcosm of yoga’s greatest challenge and greatest gift: the tension between ideal and reality, between aspiration and acceptance, between the pose we imagine and the pose we actually embody. Both Iyengar and his daughter offer us tools for navigating this tension, reminding us that the true teaching of yoga lies not in any single form but in the wisdom to know when to hold steady and when to adapt.

As we continue to practice and teach this fundamental pose, we carry forward both approaches – the unwavering commitment to excellence and the compassionate recognition of diversity. In doing so, we honor the full spectrum of what yoga can be: both a mountain to climb and a home to rest in, both a challenge to meet and a gift to receive.

Thank you for registering for Threads in Patanjali’s Wisdom online course with Dr. Agi Wittich This page contains everything you need for eight weeks

Session 3 – Threads in Patañjali’s Wisdom For Session 4: Āsana as a Path to Samādhi We explore Patañjali’s teaching on āsana, and more

Agi Wittich is a yoga practitioner since two decades, and is a certified Iyengar Yoga teacher. Wittich studied Sanskrit and Tamil at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel, completing a PhD with a focus on Hinduism, Yoga, and Gender. She has published academic papers exploring topics such as Iyengar yoga and women, the effects of Western media on the image of yoga, and an analysis of the Thirumanthiram yoga text.