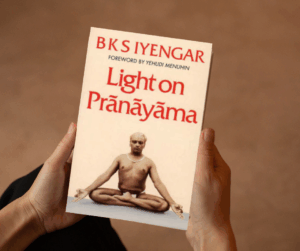

Closing Gathering for Light on Pranayama

Date and Time: May 24, 2026 8am UTC (Coordinated Universal Time) As our Yoga Readers cycle on B.K.S. Iyengar’s Light on Prāṇāyāma comes to completion, we

“Prāṇa is the vehicle of consciousness.” — B.K.S. Iyengar, Light on Life

This concise yet expansive statement from B.K.S. Iyengar reveals a foundational truth: prāṇa, often translated simply as “breath,” is in fact the dynamic force that binds the various layers of our being—from the gross physical body to the subtlest expressions of awareness. It is through prāṇa that we inhabit our form, and through prāṇa that we refine and expand our consciousness. To engage with prāṇa is to enter into a relationship with the deepest currents of life.

In the beginning of practice, breath awareness often appears as a practical instruction—”Don’t hold the breath,” “Let the breath flow freely,” “Observe the rhythm of your breathing.” But in the Iyengar tradition, these are never mere physiological corrections. They are the first invitations into a more subtle inquiry. As our practice matures, the breath ceases to be background; it becomes the very medium through which presence, steadiness, and transformation are cultivated.

Geeta S. Iyengar, in Yoga: A Gem for Women, speaks of prāṇāyāma as a cleansing and clarifying process—one that purifies the organic systems, soothes the nervous system, and directly influences the mental and emotional fields. She warns, however, that this process must be approached with delicacy and maturity. Prāṇāyāma is not forceful breathing. It is not a test of capacity. It is a process of refinement. The breath must become smooth, quiet, continuous, and subtle. When practiced in this way, the breath becomes a balm for the agitated mind, and a steady guide into the deeper realms of yogic experience.

B.K.S. Iyengar frequently emphasized that the breath and mind are reflections of one another. When the mind is disturbed, the breath is irregular; when the breath becomes steady, the mind begins to settle. This reciprocal relationship offers the practitioner a direct pathway for transformation. We cannot always change our circumstances, but we can work with the breath, and through the breath, the citta, the field of consciousness, begins to shift. In this way, the breath becomes not only a reflection of our state but an instrument for changing it.

The development of breath sensitivity begins even in āsana. When breath awareness enters the pose, we discover that the pose itself changes. The firmness (sthira) of the pose softens into steadiness, and the comfort (sukha) becomes more than physical ease. It becomes a kind of inner spaciousness. The breath teaches us to stay, not with rigidity, but with intelligent containment. It teaches us to move from reaction to response, from struggle to observation, and from observation to participation in the unfolding intelligence of the body.

As practice deepens, prāṇāyāma becomes the link between the outer limbs of yoga: āsana and yama/niyama, and the inner limbs: pratyāhāra, dhāraṇā, and eventually dhyāna. In The Tree of Yoga, Guruji writes that prāṇa is the starting point for all deeper work. Prāṇāyāma prepares the mind to turn inward. It is the threshold over which the senses begin to withdraw, and the awareness begins to collect itself in preparation for stillness. Without the breath, the inward turn is forced or artificial. With the breath, the movement is organic and luminous.

Geeta Iyengar’s work with women throughout the life cycle has shown the healing power of prāṇāyāma in practice. Whether addressing hormonal imbalances, supporting the transitions of pregnancy and menopause, or responding to the physiological exhaustion brought by caregiving and emotional strain, she taught that breath is a potent therapeutic instrument. Through practices such as Ujjāyī and Viloma, women could restore emotional equilibrium, strengthen vital functions, and reconnect with their inner resilience. These are practical gifts, handed down through experience and rigorously tested in the laboratory of the body.

Modern science now confirms what the sages have always known: that regulated, conscious breathing activates the parasympathetic nervous system, reduces stress hormones, supports cardiac health, and cultivates emotional clarity. Yet for the practitioner of yoga, prāṇa is not merely functional, it is sacred. It is the current that connects body to mind, outer to inner, effort to surrender.

And this sacred current is available not only during formal prāṇāyāma practice, but at every moment of the day. Before a difficult conversation, when caught in agitation, during transitions, or in moments of stillness, the breath is there. It waits, quietly, to be remembered. It invites us to return. To pause. To listen. And then to act from awareness.

To integrate prāṇa into daily practice does not require elaborate technique. Begin or end your āsana practice with a few quiet minutes, simply observing the breath. At first, resist the urge to control it. Let the breath reveal its rhythm, its pauses, its resistance, and its texture. And then, gently begin to smooth and lengthen the breath. Allow the inhalation to rise evenly from the diaphragm, and the exhalation to soften and empty the skin. Keep the face passive. Soften the tongue. Let the breath move not only through the lungs, but through the body’s intelligence.

In time, the breath becomes your companion. It holds the mirror up to your emotional and mental fluctuations. It stabilizes the nerves. It draws the wandering senses back home. And most importantly, it reminds you that transformation comes from attentiveness.

As B.K.S. Iyengar said, “The gift of breath is the gift of life.” We do not own the breath. We are breathed. And in that recognition lies humility, grace, and the doorway to the sacred.

If you’d like to support my work, you can Buy Me a Chai – and help keep these teachings flowing freely.

So today, ask yourself: When do you truly feel the breath as your guide? How has breath awareness changed the quality of your āsana, your presence, or your relationships? What does your breath reveal when you are disturbed, and how do you listen? What would it mean to let your prāṇa—subtle, unseen, and intelligent—lead the way?

You do not need to understand everything. You only need to begin with one breath, consciously taken.

For a deeper exploration of prāṇa as both a yogic concept and a lived experience, you’re welcome to read more in Chapter 3: Vitality – The Energy Body (Prāṇa), and in my article on myth, breath, and transformation, The Ocean of Milk: Ancient Wisdom and Yogic Breath.

Date and Time: May 24, 2026 8am UTC (Coordinated Universal Time) As our Yoga Readers cycle on B.K.S. Iyengar’s Light on Prāṇāyāma comes to completion, we

A global reading journey with B.K.S. Iyengar’s classic on the yogic art of breathing January – May 2026 on Sundays 8am UTC (Coordinated Universal

Date and Time: January 18, 2026 8am UTC (Coordinated Universal Time) In this new Yoga Readers cycle we will be reading B.K.S. Iyengar’s Light on

Agi Wittich is a yoga practitioner since two decades, and is a certified Iyengar Yoga teacher. Wittich studied Sanskrit and Tamil at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel, completing a PhD with a focus on Hinduism, Yoga, and Gender. She has published academic papers exploring topics such as Iyengar yoga and women, the effects of Western media on the image of yoga, and an analysis of the Thirumanthiram yoga text.