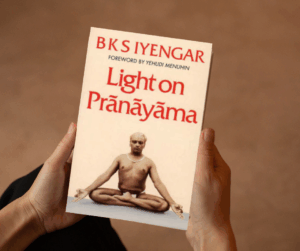

Closing Gathering for Light on Pranayama

Date and Time: May 24, 2026 8am UTC (Coordinated Universal Time) As our Yoga Readers cycle on B.K.S. Iyengar’s Light on Prāṇāyāma comes to completion, we

“Yoga is the rule book for playing the game of Life, but in this game no one needs to lose.”

This profound statement from Light on Life reframes yoga not as a practice confined to the mat, but as a deeply embodied way of living—a comprehensive ethical and philosophical system for navigating human life with clarity, compassion, and integrity. In the Iyengar tradition, the yamas and niyamas—the foundational ethical principles laid out by Patañjali—are not abstract moral codes but daily, living guidelines. They offer the first and second limbs of the aṣṭāṅga yoga path, the roots from which all higher limbs can grow.

This understanding is beautifully laid out in B.K.S. Iyengar’s metaphor of the yogic path as a living tree—roots (ethics), trunk (discipline), sap (breath), and fruit (freedom). Our study of The Tree of Yoga explores this organic model of integrated practice.

Rooted in Universality: Yama as the Foundation of Right Relationship

The five yamas are universal precepts that guide our relationship with the world. As Geeta S. Iyengar reminds us, “These are the great universal moral commandments which are not limited by birth, place, time, and occasion.”

Ahimsa (non-violence) is the cornerstone, and it extends far beyond refraining from physical harm. It invites an inner atmosphere of kindness in thought, speech, and action. As B.K.S. Iyengar writes, “The shame of violence, of harming others, is simply that it is an offence against underlying unity and therefore a crime against truth.” In asana, ahimsa guides us not to push beyond our edge with ambition, but to explore our boundaries with sensitivity and awareness.

Satya (truthfulness) calls us to align our words, actions, and internal state with reality. Guruji cautions, “Truth has got to be tempered with social grace… The sword of truth has two edges, so be careful.” In practice, this may mean acknowledging fatigue rather than masking it, or modifying a pose to reflect the reality of the moment.

Asteya (non-stealing) urges us to honor boundaries—of time, energy, resources. This includes not stealing attention, not grasping for credit, and not encroaching upon others’ space or energy.

Brahmacarya (appropriate use of energy) is often misunderstood as celibacy. In its wider context, it invites conscious channeling of all vital forces. As Geeta S. Iyengar teaches, it means “moderation in sex between married couples,” but also conserving energy through restraint in thought, speech, and daily consumption.

Aparigraha (non-possessiveness) encourages freedom from grasping—whether for material things, relationships, outcomes, or even identities. As Guruji warns, “Wealth that is not redistributed will stagnate and poison us.” This yama becomes especially powerful in our consumer-driven culture.

Personal Grounding: Niyama as the Path of Self-Cultivation

The five niyamas bring the ethical gaze inward. They guide our relationship with ourselves and support a fertile inner terrain for transformation.

Śauca (cleanliness) refers not only to physical hygiene but to purity of intention, clarity of thought, and the cultivation of sattvic (pure, luminous) conditions in our environment and inner life.

Santoṣa (contentment) teaches us to rest in the sufficiency of the present moment. As Guruji writes, “It gives a poised mind which results in pure happiness.” It is not passive acceptance but an active choosing of peace.

Tapaḥ (austerity or discipline) is the fire of practice that burns impurities and builds will. Geeta Iyengar describes it as “the conquest of all desires by practising purity in thought, speech, and action.” It is the container in which deeper awareness can ripen.

Svādhyāya (self-study) is both inner reflection and study of sacred texts. It trains the mirror of awareness to become ever more accurate. It is not self-judgment, but deep observation.

Īśvara Praṇidhāna (surrender to the divine) invites humility, the willingness to relinquish the illusion of control and open to something greater. This is the heart’s bow to the unnameable.

This is the heart’s bow to the unnameable. In exploring this surrender more deeply, we reflect on how different yogic voices—including Iyengar’s—frame faith not as blind belief, but as a lived, embodied openness to that which is greater than the ego. Read more on this in my article “Īśvara Praṇidhāna and Perspectives on Faith.”

These niyamas help cultivate the vijñānamaya kośa, the wisdom layer of our being, explored more deeply in our reflections on Vijnāna: The Intellectual Body.

Embodied Ethics: Practice Beyond the Mat

Ethical practice is not an appendage to asana; it is the ground from which right action arises. As Guruji reminds us, “The awareness that yoga cultivates can improve our lives in many practical and life-changing ways.” This could mean regulating desires in the supermarket (aparigraha), speaking kindly when we feel irritated (ahimsa), or returning to our breath before reacting (tapas and svādhyāya).

Through āsana and prāṇāyāma, we train the nervous system to become a vessel of steadiness and clarity, from which ethical discernment becomes not only possible but natural. Our actions align with our values. The ethical foundation becomes lived.

This connection between structure and lived inner freedom is explored further in “Finding Freedom Within Structure”, where we consider how discipline—far from being restrictive—can open the way to authenticity and ethical fluidity.

Ultimately, ethical living opens the door to true freedom—not freedom as indulgence, but as inner spaciousness and responsibility. This is the theme of our reading in “Chapter 7: Living in Freedom”, which explores how living in alignment with yama and niyama sets the stage for liberation rather than limitation.

The Feminine Lens: Ethics in the Flow of Life

Geeta S. Iyengar’s contributions bring these ethics into vivid focus for modern practitioners. She demonstrates that ahimsa includes recognizing hormonal cycles and emotional tides. She shows how tapas can manifest as the discipline to rest when needed. Her teachings illuminate that living ethically is not about strict enforcement, but intelligent application—a rhythm, not a rule.

Whether during pregnancy, menstruation, menopause, or through life’s various transitions, the ethical principles of yoga remain alive, flexible, and responsive. Her words echo with timeless relevance: “Yoga helps woman to fulfil her tasks as well as to maintain her complexion, lustre, and femininity.”

Daily Practice: Choose an Ethical Focus

In your next 24 hours, select one yama or niyama and observe how it manifests in your actions, speech, thoughts, and reactions.

How does santoṣa shift your response to disappointment?

Can satya refine your internal alignment and deepen your honesty in a posture?

Does aparigraha help you let go of something unnecessary—be it tension, expectation, or self-judgment?

Remember, yoga is not about perfection. It is about practice—conscious repetition with compassion.

Let your ethical inquiry guide your steps on and off the mat.

If you’d like to support my work, you can Buy Me a Chai – and help keep these teachings flowing freely.

Reflective Questions for Ethical Living:

Which ethical principle do you find most resonant—or most difficult—at this moment in your life?

In what ways does your physical practice of yoga support or challenge your ability to live ethically?

How might your life change if you approached each day as a field for practicing yama and niyama, rather than waiting for a quiet hour on the mat?

Date and Time: May 24, 2026 8am UTC (Coordinated Universal Time) As our Yoga Readers cycle on B.K.S. Iyengar’s Light on Prāṇāyāma comes to completion, we

A global reading journey with B.K.S. Iyengar’s classic on the yogic art of breathing January – May 2026 on Sundays 8am UTC (Coordinated Universal

Date and Time: January 18, 2026 8am UTC (Coordinated Universal Time) In this new Yoga Readers cycle we will be reading B.K.S. Iyengar’s Light on

Agi Wittich is a yoga practitioner since two decades, and is a certified Iyengar Yoga teacher. Wittich studied Sanskrit and Tamil at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel, completing a PhD with a focus on Hinduism, Yoga, and Gender. She has published academic papers exploring topics such as Iyengar yoga and women, the effects of Western media on the image of yoga, and an analysis of the Thirumanthiram yoga text.