Special Session with Stephanie Quirk on Pranayama

Date and Time: March 8, 2026 9:30am UTC (Coordinated Universal Time) I’m delighted to host an inspirational talk about prāṇāyāma with Stephanie Quirk, one

In the vast and intricate repertoire of yoga āsanas (postures), Śavāsana (Corpse Pose) holds a unique and profoundly significant position. Often superficially perceived as a simple end-of-practice rest, its mastery reveals the deepest tenets of yogic philosophy and self-realization. As Geeta S. Iyengar emphasizes in Yoga: A Gem for Women, “Although Śavāsana appears simple, it is most difficult to master. The body and the mind are interdependent and interconnected. They are inseparable in the art of introspection.” This highlights Śavāsana not as a passive state, but as an active and challenging practice of conscious relaxation.

The Bridge Between Worlds: Integrating Practice

The significance of Śavāsana extends far beyond mere physical repose. Geeta S. Iyengar elaborates on its pivotal role: “Śavāsana is a link connecting the body and the mind; it connects āsana and prāṇāyāma and leads one to the spiritual path.” This understanding positions Śavāsana as a crucial bridge, a sandhi (junction) between the more external, gross practices of physical āsana and the more internal, subtle practices of prāṇāyāma (breath control) and dhyāna (meditation). It is where the active engagement of the annamaya kosha (physical sheath) and pranamaya kosha (energetic sheath) gradually recedes, allowing the practitioner to delve into the manomaya kosha (mental sheath) and beyond.

The Meticulous Art of Unfurling: Precision in Repose

The practice of Śavāsana demands meticulous attention to detail and a profound level of internal awareness, a precision that is characteristic of the Iyengar method. Every aspect of the body must be consciously adjusted and released—from the broadening of the shoulders to the precise placement of the head. As Geeta S. Iyengar instructs, one must “Broaden and flatten the buttocks so that the flesh in this area does not become tight, especially in the small of the back.” Similarly, attention is drawn to the head: “Move the hands towards the head to adjust it and place the back of the head centrally on the floor.” Even the angle of the arms and the softness of the hands are crucial, ensuring that “the shoulders come off the floor and are contracted” or that the chest is not hindered from broadening. This conscious engagement distinguishes Śavāsana from ordinary rest or sleep.

The Paradox of Conscious Stillness: An Experience of Life and Death

Perhaps most profound is Śavāsana‘s deeper, almost paradoxical, significance: “Śavāsana is like an experience of death in a living state. For a brief period the body, the mind, and the speech are still… Unlike in the dead body, however, the soul exists – it exists in a pure state.” This temporary transcendence of the active ego (ahamkara) and the cessation of external mental fluctuations (citta vrttis) creates what Geeta S. Iyengar calls “a new state of consciousness, with no movement and so no waste of energy.” It is a state where the practitioner moves beyond the vyavaharika (mundane) consciousness to glimpse the pure purusa (Soul), even for a fleeting moment.

B.K.S. Iyengar, in Light on Life, further elaborates on this profound state, describing Śavāsana as being “about shedding, in the same way that I earlier mentioned the snake sloughing off its old skin to emerge glossy and resplendent in its renewed colors.” It is a shedding of “many skins, sheaths, thoughts, prejudices, preconceptions, ideas, memories, and projects for the future,” leading to a unique sense of being “present and formless.”

The Subtle Breath and The Inner Gaze

The relationship between body and breath takes on particular importance in Śavāsana. “The movement of breathing should not disturb the trunk, the limbs, and the brain,” Geeta S. Iyengar emphasizes. This deep, subtle awareness of breath leads to what she describes as “perfect relaxation, where the mind remains unperturbed and an inward flow of energy is experienced.” The breath becomes a quiet anchor, supporting the inner journey. This subtle interplay of body, breath, and mind is essential to Śavāsana’s effect and is beautifully unpacked in my BKS Iyengar’s book “Light on Life” Chapter 3: Vitality – The Energy Body, where the movement of prāṇa and its calming impact are emphasized.

The practice involves systematic relaxation of every part of the body, from the grossest to the most subtle. “Relax the skin of the forehead, the cheeks, the lips, the hands, the sides of the trunk, the buttocks, and the thighs,” Geeta instructs. However, this relaxation is not passive dullness. Rather, it is a state of “alert passivity” where one learns to “direct the brain and the eyes towards the heart centre.” This active, yet relaxed, inner awareness distinguishes Śavāsana from ordinary rest or sleep. B.K.S. Iyengar clarifies in Light on Life that true meditation, to which Śavāsana is a gateway, is “luminous, aware.”

The Mental Landscape and Ultimate Surrender

The mental aspect of the practice is equally crucial. “The interrelation of the eyes, the mind, and the brain is very important,” Geeta S. Iyengar explains. “If the mind wanders, the brain moves upward and the eyes too become unsteady.” The practitioner must diligently learn to “draw in the eyes and ears, draw them inwards and fuse them at a point inside the centre of the chest where external sounds cease to disturb.” This is a conscious act of pratyahara (sense withdrawal), essential for stilling the manomaya kosha.

The ultimate goal is a profound act of letting go, of true vairagya. As Geeta S. Iyengar describes, it is to “surrender yourself, your body and mind to Mother Earth so that you are calm and passive. This is total relaxation.” Through this surrender, one experiences what she calls “freedom of the mind and freedom of the body.” The benefits are comprehensive and transformative. “Śavāsana is invigorating and refreshing,” Geeta notes. “It helps the body and the mind to recuperate after long and serious illnesses.” She particularly emphasizes its value for those suffering from “respiratory diseases, heart trouble, nervous tension, and insomnia” as it “soothes the nerves and calms the mind.” Such restorative capacity makes Śavāsana particularly supportive across women’s life stages—from pregnancy to menopause—as discussed in Women’s Life Cycles: A Yogic Perspective.

Most importantly, Śavāsana is not just about physical rest but about consciously entering a state of meditative awareness (dhyana). As Geeta S. Iyengar concludes, “It is not simply lying flat on the back. It is a state of meditation.” Through regular, dedicated practice, one learns to access deeper levels of relaxation and inner stillness while maintaining conscious awareness, making Śavāsana truly “control over the inner world and surrender to the Supreme Being.” The mastery of Śavāsana requires patience, dedication, and systematic practice, opening a profound gateway to understanding the subtle relationship between body, breath, and consciousness.

If this article nourished your practice, feel free to Buy me a chai to support more in-depth yogic explorations.

Questions or reflections about Śavāsana? Talk yoga to Agi—I’d love to connect and support your journey

Reflective Questions for Your Śavāsana Practice:

Date and Time: March 8, 2026 9:30am UTC (Coordinated Universal Time) I’m delighted to host an inspirational talk about prāṇāyāma with Stephanie Quirk, one

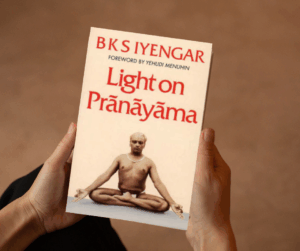

Date and Time: May 24, 2026 8am UTC (Coordinated Universal Time) As our Yoga Readers cycle on B.K.S. Iyengar’s Light on Prāṇāyāma comes to completion, we

A global reading journey with B.K.S. Iyengar’s classic on the yogic art of breathing January – May 2026 on Sundays 8am UTC (Coordinated Universal

Agi Wittich is a yoga practitioner since two decades, and is a certified Iyengar Yoga teacher. Wittich studied Sanskrit and Tamil at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel, completing a PhD with a focus on Hinduism, Yoga, and Gender. She has published academic papers exploring topics such as Iyengar yoga and women, the effects of Western media on the image of yoga, and an analysis of the Thirumanthiram yoga text.