Private Iyengar Yoga classes

Private Iyengar Yoga sessions offer an opportunity for focused, individualized work, tailored precisely to your needs, physical condition, and stage of practice. In

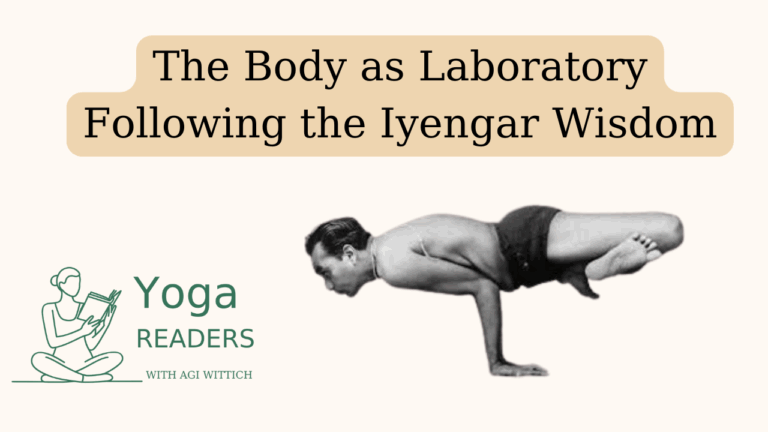

“To a yogi, the body is a laboratory for life, a field of experimentation and perpetual research.”

—B.K.S. Iyengar

This insight from Guruji is not a metaphor but a method. In the Iyengar tradition, the mat is not a stage for performance but a space for inquiry. Practice becomes an evolving process of observation, discrimination, and transformation—not only of the asana, but of the self.

When we begin to work in this way, the asana is no longer a static shape to be achieved but a living structure in which we investigate alignment, balance, directionality, and integration. The body becomes the first site of research—annamaya kosa—through which we gradually access deeper sheaths: breath (pranamaya), mind (manomaya), intelligence (vijnanamaya), and eventually bliss (anandamaya).

As Guruji writes in Light on Life:

“The light that yoga sheds on life is something special. It is transformative. It does not just change the way we see things; it transforms the person who sees.”

This transformation does not happen by chance. It is the result of disciplined practice (abhyasa), guided by discriminative intelligence (viveka) and inner sensitivity. Our method is precise and our tools are subtle. “Each pore of the skin becomes an eye,” Guruji taught. Through such heightened perception, we learn to differentiate between effort and strain, stability and rigidity, sensitivity and indulgence.

Geeta S. Iyengar, in Yoga: A Gem for Women, reminds us that intelligent practice is always responsive. The research must adapt to the practitioner:

“The practice should be adapted to the particular needs and conditions of women.”

This is not merely a physiological consideration—it is epistemological. True research honours the subject. Whether we are exploring cyclical changes, stages of life, or emotional and physical limitations, we must listen deeply. There is no one-size-fits-all method in authentic yogic inquiry.

Cultivating the Inner Researcher

Our laboratory demands not only technique, but gunas—qualities of the mind and heart.

In this way, the practitioner and the practice are not separate. The mat becomes the ground where the inner scientist and the living subject meet—attentively, intelligently, and compassionately.

As Geetaji writes, practice is not only about achievement but about care, insight, and transformation across the lifespan:

“It’s about cultivating a practice that supports health, vitality, and spiritual growth throughout all stages of a woman’s life, acknowledging her inherent capacity for resilience and transformation.”

Your Lifelong Sādhana of Discovery

Each time you step onto your mat, you engage in profound research. You are simultaneously the observer and the observed. You are not merely “doing” yoga—you are studying the Self through the medium of the body, breath, and mind.

This laboratory is open every day. Enter with humility, proceed with clarity, and allow your discoveries to permeate not only your āsana but your way of being in the world.

If this article inspired you and you’d like to support more writing like this, you can Buy Me a Chai and help nourish this work.

For Reflection:

Read more about the Four stages of Yoga practice.

Private Iyengar Yoga sessions offer an opportunity for focused, individualized work, tailored precisely to your needs, physical condition, and stage of practice. In

A special offering for Light on Prāṇāyāma readers We’re happy to offer this 5-session online prāṇāyāma course with senior Iyengar teacher Stephanie Quirk at

At the opening of Light on Prāṇāyāma, B.K.S. Iyengar invokes Hanumān [हनुमान्]. The reference is brief, almost passing, yet it is not incidental. Iyengar

Agi Wittich is a yoga practitioner since two decades, and is a certified Iyengar Yoga teacher. Wittich studied Sanskrit and Tamil at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel, completing a PhD with a focus on Hinduism, Yoga, and Gender. She has published academic papers exploring topics such as Iyengar yoga and women, the effects of Western media on the image of yoga, and an analysis of the Thirumanthiram yoga text.